The results have researchers wondering if doses can be reduced even further.

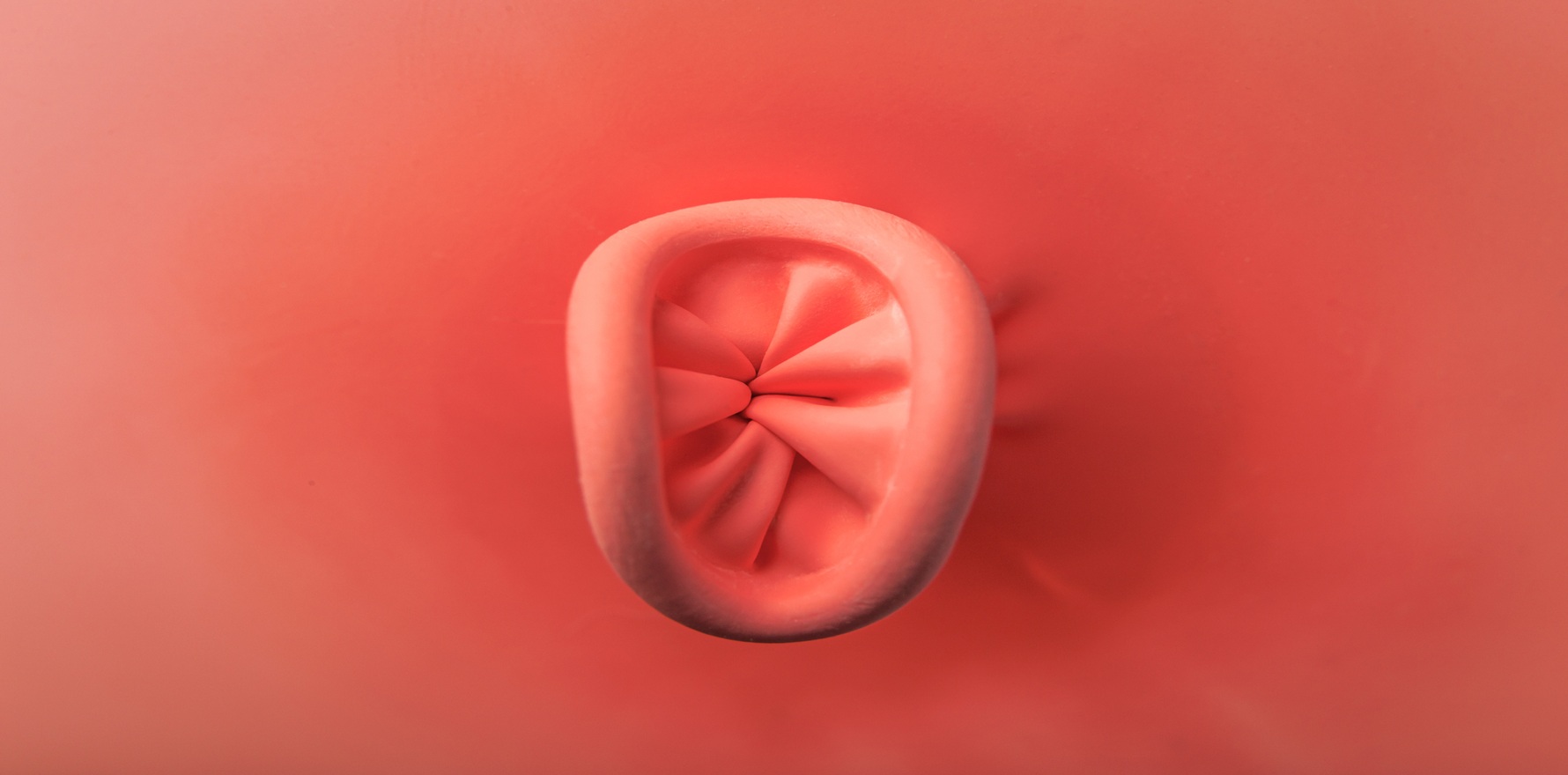

A smaller dose of radiotherapy improves quality of life while achieving a similar clinical response rate in a specific cohort of anal cancer patients.

Treatment approaches for anal cancer over the past three decades have been relatively consistent, where all patients receive a similar dose of radiotherapy regardless of the size of their tumour.

But the results of the Personalising Radiotherapy in Anal Cancer (PLATO) trial, published in The Lancet Oncology and presented at the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology congress in Austria earlier this month, suggest a reduced dose of radiotherapy is just as effective as the standard dose, and is accompanied by fewer side effects.

“The results will transform the lives of patients with early-stage anal cancer by using a shorter, lower dose of radiotherapy that does not compromise cure rates and reduces the side effects of treatment,” said David Sebag-Montefiore, professor of clinical oncology at the University of Leeds and the study’s chief investigator, in a statement.

“The shorter, highly effective radiotherapy course not only reduces side effects; it reduces hospital visits and optimises the use of healthcare resources.”

As part of the PLATO trial, 160 patients with early-stage squamous cell anal carcinoma (T1-2, where the tumour is ≤ 4cm in size) were recruited from 28 referral centres across the UK and randomised to receive either standard- (50.4 Gy in 28 fractions) or reduced-dose (41.4 Gy in 23 fractions) intensity-modulated radiotherapy in a 1:2 fashion. The majority of patients were female (73%) and were deemed to be high-risk HPV positive (85% of evaluable samples).

Complete clinical response rates – defined as a tumour regression grade score of one or two, or where patients were deemed to have a complete response if clinical assessment was the follow-up undertaken – were similar between the two radiotherapy doses at the six-month follow-up: 84% after sd-IMRT and 85% after rd-IMRT.

Responses to patient-reported quality of life measures, including global health and sexual functioning, followed largely similar trajectories in both groups – returning to baseline levels within six weeks of treatment finishing and continuing to improve until the six-month mark. However, both men and women in the sd-IMRT group reported poorer sexual functioning after six months.

Forty-six percent of patients in the sd-IMRT group experienced at least one grade 3 or worse adverse event compared to 35% in the rd-IMT group. The most commonly reported grade 3 or worse adverse events were radiation dermatitis, diarrhoea and neutropenia. Radiotherapy interruptions due to treatment toxicity were rare, occurring in 9% of patients in the sd-IMRT group and 4% of patients in the rd-IMRT group.

“Given the improvements in compliance and tolerability of the de-escalated regimen in older patients, with preserved early cancer outcomes, this reduced-dose regimen could be considered a new treatment option for frailer patients not fit for standard-dose chemoradiotherapy,” the researchers wrote in The Lancet Oncology.

Longer-term follow-up data presented at the ESTRO congress were consistent with the earlier responses; 88% of patients who received rd-IMRT were cancer-free after three years, compared to 84% in the sd-IMRT group. Fewer side effects were also reported by rd-IMRT patients

“For the first time, we can see the true impact of anal cancer and treatment from the patient point of view using the two treatment approaches. We also see a trend towards improved sexual function in the longer term for men and women using the shorter, lower dose treatment,” said Associate Professor Alexandra Gilbert, who presented patient-reported quality of life data at ESTRO.

Dr Penelope De Lacavalerie, a consultant colorectal, robotic and general surgeon from Sydney, said the improvements in sexual and bowel function were important findings, and would have significant impacts on the patient’s quality of life.

“The majority of people with anal cancer are gay men, many of whom live with HIV. We know that HIV has chronic effects on the immune system and affects the quality of life, so it’s important to know that we’re not decreasing the amount of treatment or impairing survival by giving them less [radiation therapy], but we are improving their quality of life,” the Bowel Cancer Australia spokesperson explained.

Related

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Cancer data in Australia report estimated that 611 people were diagnosed with anal cancer in 2024 at an age-standardised rate of 2.3 cases per 100,000 people, making it one of the rarer cancers recorded in the country.

Dr De Lacavalerie said there were multiple reasons why it had taken so long for a more personalised treatment approach to make its way to the anal cancer population.

“[First,] it was only in the last three years that we have moved from just diagnosis cancers to diagnosing precancerous lesions and then stopping them from progressing. Before this, it seemed that when people were diagnosed with anal cancer, it was almost too late,” she explained.

“Second, anal cancer is more common in targeted populations, such as those living with HIV. So, treating people with anal cancer is almost like a taboo [for some people]. Lots of people who are diagnosed with anal cancer also tend to say they have colon or bowel cancer, so it’s [probably] underreported.”

One of the limitations of the study was that local recurrence was not assessed with high-resolution anoscopy, an approach recommended in the anal cancer screening guidelines for people living with HIV that were released earlier this year.

“HRA is a procedure that is not widely used yet, and there is a lack of providers who do it. To put it in perspective, I’m one of probably five [clinicians] in Sydney that does HRA. There is a need to train people in this technique,” said Dr De Lacavalerie.

“Long gone are the days where the patient comes in, you put your finger in [as part of a digital anorectal exam] to see if you can feel anything, and then off you go. That’s not enough, because the precancerous lesions, or the lesions that come back after having anal cancer and undergoing chemoradiation aren’t palpable until it’s too late.

“Although the authors did mention that HRA will be done in another follow-up study after this, where they are considering using even lower doses of radiotherapy because they found such a good response in this study. It’s important that we are moving with the times.”