Find out which six cancer types are sharply increasing in incidence in young Australians – and which two are booming in older adults.

Findings from a new international study have experts calling for more personalised assessments and treatments in people with cancer.

There is significant concern regarding the increase in cancer rates among younger adults. Consequently, changes to the incidence of cancer in older adults can sometimes fall to the wayside.

But a new international comparative study, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, aims to change this, specifically comparing – and finding – differences in the direction and magnitude of cancer incidence trends in both younger and older adults.

“This analysis demonstrates an increase in cancer burden across the adult age spectrum,” Associate Professor Christopher Cann and Dr Efrat Dotan, a pair of oncologists from Philadelphia in the United States, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Therefore, the contemporary concern about increasing cancer rates should recognise that this increase is not restricted to young adults but affects all generations.”

Researchers used data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s Global Cancer Observatory Database from 42 countries over a 15-year period. There was a diverse list of countries included in the review (e.g., Australia, the United States, Israel, Uganda, Qatar, Italy, Finland, Thailand and Argentina).

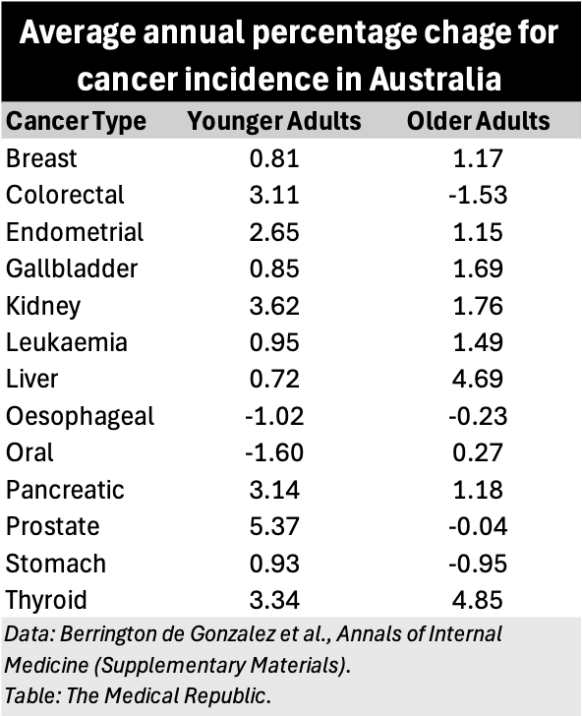

The researchers explored the average annual percentage change (AAPC) of 13 different types of cancer: leukaemia and colorectal, stomach, breast, prostate, endometrial, gallbladder, kidney, liver, oesophageal, oral pancreatic and thyroid. Importantly, they estimated the AAPC for each kind of cancer in both younger (20-49 years) and older (50 years and up) adults.

Increases in cancer incidence were observed in six of the 13 cancer types in younger adults: thyroid cancer (median increase 3.6%), kidney (2.2) cancer, endometrial cancer (1.7%), colorectal cancer (1.5%), breast cancer (0.9%) and leukaemia (0.8%). Similar trends were seen in older adults, with the incidence of five of these six types also increasing: thyroid cancer (3.0%), kidney cancer (1.7%), endometrial cancer (1.2%) breast (0.9%) and leukaemia (0.6%). There was no increase in the AAPC of colorectal cancer in older adults.

Prostate and pancreatic cancer incidence rates also increased in both younger and older adults (3.2% and 0.75% for prostate cancer, and 1.0% and 1.0% for pancreatic cancer), while the incidence of gallbladder cancer increased in young adults but not older adults (0.5% versus -0.1%). In contrast, liver, oral, oesophageal and stomach cancer incidence rates decreased in younger adults (-0.1%, -0.4%, -0.9% and -1.6%). Older adults saw increases in the incidence of liver and oral cancers (2.2% and 0.5%) but decreases in stomach and oesophageal cancers (-2.1% and -0.3%).

When only the Australian data were considered, a similar picture emerged. The incidence of certain cancers increased in both younger and older adults, while others increased in younger adults but decreased in older adults.

Professor Cann and Dr Dotan emphasised the importance of understanding the biological differences between different types of cancer in younger and older adults to ensure the most effective treatment options are used in each population as they are developed.

“We must also recognise the differences in treatment tolerance by age and associated comorbidities,” they wrote.

Related

“There is an under-recognised and understudied nuance in the treatment of patients at each end of the age spectrum.

“Although younger patients typically have lower comorbidity and higher physiologic resilience, they face complex psychosocial and supportive care needs secondary to disruptions in the development of body image, financial security, career development and family planning. These needs make them distinct from paediatric and older adult patients and poorly served by traditional cancer care models.

“On the other hand, older adults can experience overtreatment and undertreatment due to inaccurate assumptions about organ function and potential treatment tolerance. Geriatric assessments can provide a better understanding of the patient’s biological age to guide treatment decisions, predict tolerance and improve communication for older adults with cancer.”