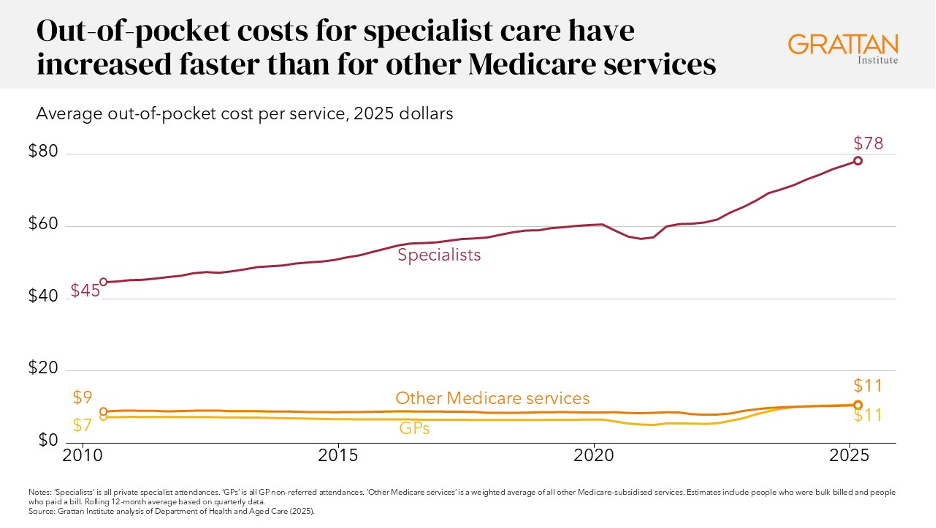

Non-GP specialist fees have risen by about 75% since 2010, according to a new report from the public policy think tank.

The Grattan Institute has come out with a bold new proposal to remove Medicare funding from non-GP specialists who charge “excessive” patient fees as part of a new report focused on improving access to care.

According to the paper, one of the most direct ways to increase accessibility would be to require non-GP specialists who charge more than triple the MBS schedule fee to repay all Medicare rebates to the government at the end of the financial year.

What’s more, the report also recommended publicly naming doctors who charge extreme fees to give GPs and patients more information prior to making a referral.

All told, though, extreme-fee-charging doctors represent around 4% of all non-GP specialists.

This option has been endorsed by Private Healthcare Australia (PHA), the industry group representing private health insurers.

PHA CEO Dr Rachel David called initial appointment fees of $1000 or more a “massive barrier to private hospital care”.

“Health insurers cannot keep paying private hospitals more and more to help them through a difficult period if the key to their survival rests with doctors,” she said.

“When health insurers provide funding to private hospitals for no service, it drives up the cost of health insurance for millions of Australians for no public benefit.”

Grattan Institute health program director Peter Breadon told Oncology Republic that – while the extreme fee payback proposal was certainly the juiciest aspect of the report – there was no “one weird trick” to make specialist care accessible in Australia.

“Boosting public sector capacity in the areas that need it most is probably one of the … highest impact things you could do,” he said.

In practice, this would look like enshrining a minimum level of specialist care in the upcoming renegotiation of the National Health Reform Agreement, as well as expanding public services in areas of the country which are in the bottom 25% of services per person.

Doing so would entail a level of flexibility and coordination between state and Commonwealth government.

From a budgetary standpoint, it is predicted to cost $470 million a year to provide an extra 984,000 public specialist services in the most under-served areas.

“The system is … running on autopilot in the sense that training is largely dictated by precedent, inertia and the immediate needs of hospitals and colleges,” Mr Breadon said.

“The distribution of public services isn’t really matched to the balance of supply and demand to different parts of Australia.

“[When we talk about reform,] it’s really about this re-orientation towards … ‘let’s focus training where it’s needed, let’s put services where they’re needed’.

“Then there are some nice things like secondary consultations that you can [implement] that don’t require that change in orientation towards managing the system more strategically.”

The secondary consultation pathway proposed by the Grattan Institute would see state governments set up a system that enables GPs to seek written advice from hospital specialists and the federal government provide financial incentives for GPs to use it.

Ideally, this would lead to fewer patients being referred to non-GP specialists.

According to the Grattan’s modelling, this could avoid roughly 70,000 referrals each year across the public and private systems and save patients about $4 million in specialist fees.

The report also took aim at specialist medical colleges, which it said had too much control over the workforce.

“Colleges are not set up to solve workforce shortages,” the paper read.

“They are led by members, whose interests may not align with broader system goals.

“And colleges’ expertise is in their specialty’s skills and knowledge, not the system-wide effects of training and accreditation decisions.”

Its proposed fix was to tie specialist training places to community needs, with training funding tied to meeting certain goals.

The medical specialties that were identified as particularly under-supplied – namely dermatology, psychiatry and ophthalmology – were also among some of the most expensive to access.

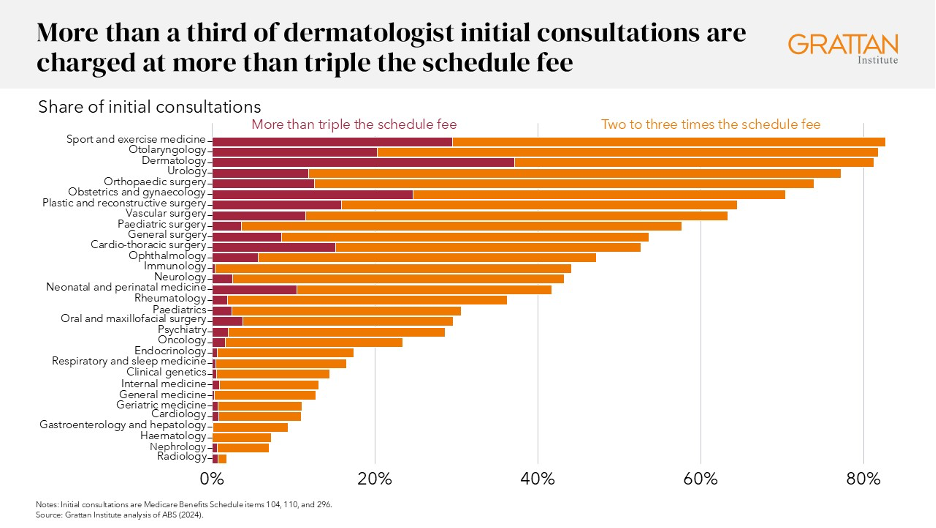

More than one third of dermatology initial consults, for instance, were charged at more than triple the schedule fee.

When it came to the median cost of an initial appointment, psychiatry took the top spot at around $250, followed by sport and exercise medicine and dermatology.

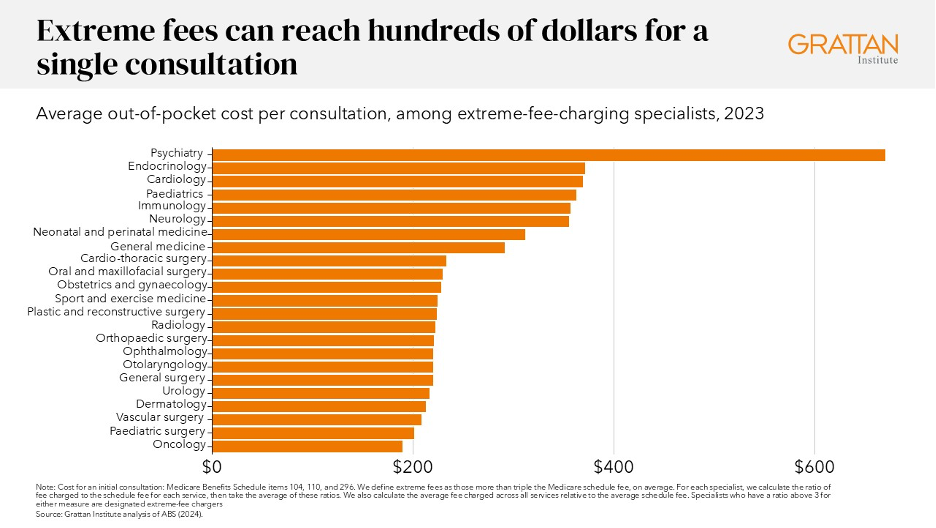

“The average out-of-pocket cost for a single consultation with an extreme-fee-charging specialist exceeded $200 for almost every specialty in 2023,” the report said.

“Some are even higher.

“A single consultation with an extreme fee-charging psychiatrist was $670 in 2023, and $350 for endocrinologists and cardiologists.”

Given that the median non-GP specialist clinic is more profitable than the median GP, legal, finance or construction business, the Grattan estimated that the doctors charging extreme fees would have an income “well above” the level needed to attract even the most highly-trained professionals.

“There can be legitimate reasons that some doctors will charge more – they might have higher rent and overheads … they might have more experience,” Mr Breadon said.

“But for these extreme outliers, it’s very hard to find any legitimate justification.”

In all, the extreme outliers represent about 1500 non-GP specialists across 29 specialties.

This is not an easy area to influence.

There are no policies or regulations that limit the fees Australian doctors can charge.

Making such a law directly, the Grattan report noted, could be open to legal challenges.

Kicking extreme-fee-charging doctors off of Medicare, meanwhile, was estimated to leave patients exposed to even larger costs.

Introducing bulk-billing incentives for specialists was considered, but the Grattan noted that this would ultimately be a very expensive exercise, as the value of the incentive would have to exceed what each non-GP specialist would have otherwise charged.

As a result, only the specialists charging the smallest out-of-pocket costs would likely be tempted to bulk-bill, doing nothing about the extreme outliers.

Increasing the Medicare rebates for specialist appointments was also considered unlikely to affect the extreme-fee-chargers.

By process of elimination, the Grattan report settled on recommending that the non-GP specialists who charge patients triple the Medicare rebate be required to repay the government portion of the patient fee each year.

The Grattan estimated this measure would raise up to $170 million in revenue, which could be directed towards the expansion of public clinics.